Courtesy of C. Levin

Embracing the controversial and the perverse, Princess Salomé, legendary in Biblical tales for her provocative “Dance of the Seven Veils”, had viciously demanded she be given the head of John the Baptist as incentive to perform. Whereas John was said to have true spiritual credentials as the supposed baptizer of Jesus, Salomé had been admired for her looks and depicted that way by artists for time immemorial. Oscar Wilde and J.-K. Huysmans, two late-nineteenth-century literary figures, were both struck by Salomé’s character and her story. While Wilde sharply maintained his focus on beauty and aesthetics. Huysmans, in contrast, zeroed in on the decadent.

MUSÉE D’ORSAY

Caroline and I are at Musée D’Orsay to see Huysmans: From Degas to Grünewald. A visual realization of the late 19th-century writings of Joris-Karl Huysmans.

UlyssePixel/Shutterstock.com

Gare D’Orsay, an historic beaux-arts railroad station in Paris, was closed in 1973. But its stunning, fin de siècle structure with its pink marble walls soon experienced a deserved reincarnation. By reopening in 1986 as Musée D’Orsay, its great halls reemerging as a series of stunning galleries.

In February 2020, Covid-19, although stealthily present, had yet to officially strike Europe or North America. Accordingly, neither Caroline nor I nor anyone else had yet to hear of social distancing. Face masks didn’t exist. Quite simply who knew? Unbeknownst to the populace at large, the outbreak insidiously lurked just around the corner. Within mere days of our visit to the museum, the virus erupted into a full-blown pandemic and an accompanying panic would set in.

Courtesy of C.Levin

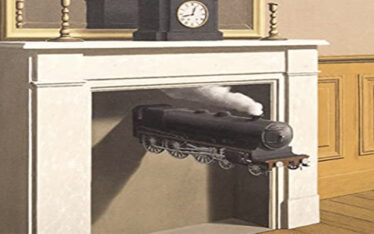

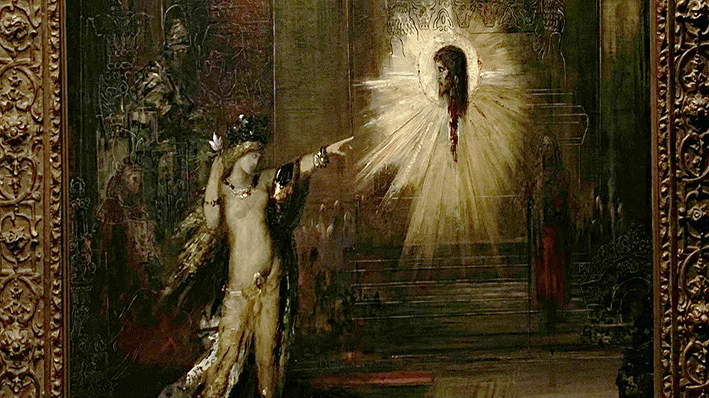

Näive and unaware, we beheld Francesco Vezzoli’s Tortoise de Soirée bronze sculpture amidst the museum’s pink marble dividers. Huysmans described it in À Rebours (Against Nature) as collapsing beneath the weight of the glittering gemstones embedded in its shell. Vezzoli served, here, as an art director. Just as Huysmans famously transforms artist’s visions into words, Vezzoli transforms them back into visual art. In this vein, walls of the exhibition and the carpet soon appeared as red as the ones described in Huysmans À Rebours. We stood there studying “The Apparition”, an impressive watercolor by French symbolist Gustave Moreau that depicted Salomé as she danced beneath an electrifying glow from the severed head of John the Baptist (see above).

THROUGH EYES OF OTHERS

Salomé has proven a truly intriguing figure for the modern creative community, the subject of works by Filippo Lippi, Rogier van der Weyden, Titian, Gustave Moreau, Aubrey Beardsley, Stéphane Mallarmé, Oscar Wilde and Richard Strauss.

Coming from a broken family, Salomé was desired by Herod, her stepfather/uncle, and used by Heroidias, her mother. Love, forever absent or perverted, she came across as cold, ruthless and uncompromising, totally used to having everything her way. But we learn how her satisfaction could have been so easily bought.

Were this whole crisis were to occur today, it most likely would be subject to an endless array of high-stakes lawsuits and countersuits. Although, granted, each principal surely would get to cherish a moment on center stage to express his or her opinion before the court.

EMOTIONS

Salomé Dancing Before Herod. Courtesy R.L.

Herod, the King or Tetrarch of Judea, fears John’s saintly powers and keeps the holy man imprisoned. He has John locked underground in a cistern beneath the king’s Galilee palace.

Although by then married to Herodias, Salomé’s mother, Herod cannot keep his eyes off his beautiful young stepdaughter. Totally obsessed, the Tetrarch presses Salomé to dance for him on his birthday. Were this happening in today’s age of “Me Too”, Herod might have had to defend himself against harassment charges. Salomé, however, possessed little interest in Herod or his wealth and power. Rather she was physically attracted to John. But the holy man quickly spurned her. Earlier he also had spurned Salomé’s mother because of her prior marriage to Herod’s late brother Phillip, who happened to have been Salomé’s father.

REJECTION

“Dance for me, Salomé, I beseech you,” pleaded Herod in Wilde’s play. “If you dance for me you may ask of me what you will, and I will give it you, even unto the half of my kingdom.” Salomé remained relentless in her refusal despite Herod’s endless attempts to dissuade her. Only grudgingly did she finally acquiesce and agree on the condition Herod was to deliver to her the head of John the Baptist.

Herod finally gave in, convinced his reputation would have been shattered if he broke his word. So, he agreed to execute John and subsequently deliver his severed head to Salomé. When given John’s head on a silver charger, Salomé lovingly strokes the holy man’s lifeless face and hair then kisses his lips… “Open thine eyes! Lift up thine eyelids, Iokanaan! Wherefore dost thou not look at me? Art thou afraid of me, Iokanaan, that thou wilt not look at me?” In Wilde’s play, Salomé knows John’s severed head can no longer deny her or her passion.

Herod’s face, as Gustave Moreau depicted it in detail, implies the Tetrarch’s disgust and anger. In contrast, Moreau shows Queen Herodias’ inherent pleasure. Salomé’s earlier feeling of dejection eases as Wilde observes: “The mystery of love is greater than the mystery of death.” Salomé’s newfound passion was reflected in her brilliant likeness that Moreau created.

As Huysmans wrote: “There was one artist above all others whose talent revealed him in a transport of ecstasy: Gustave Moreau.” 1. “The decadence of Huysmans’ artistic universe –and in particular that of his protagonists – is the maladie fin de siècle, marked by egocentricity, world-weariness and a perverse imagination.”2. On the other hand, “Moreau exploits the visual medium to achieve a fluid, but harmonious fusion of the aesthetic and spiritual levels in a single image.”3.

INFLUENCES

Before the second half of the nineteenth century, Salomé was seen mainly in paintings that reflected “the sharp contrast between… [her] idealized beauty and the violence she caused.” 4.

Huysmans was equally infatuated by and critical of Salomé. He cherished both Moreau’s colorful imagery of Herod’s stepdaughter and the sharp dialogue in Oscar Wilde’s 1892 one-act play Salomé , written in French, about her cold-blooded request. Even Huysmans own fictional character creations were openly critical of her.

MOREAU

Courtesy Moreau Museum

Paris air, by now, had grown much heavier; the traffic lighter. Protective facial masks had started to appear everywhere. We even had to mask up before heading to Musée Moreau, the artist’s former home and studio, to view the part of his collection devoted to biblical and mythological works. As we climbed the cramped circular stairs to the upper floors at the museum rich with symbolism, we were amazed how prolific Moreau had been. How infatuated he had been with the impact of Salomé.

MISGUIDED VIRTUES

Far too many believe beauty has long equaled power. People have forever been obsessed with looking as beautiful as they conceivably can. Even if it involves cosmetic surgery. Or other physical alterations or adjustments. In 2021, beauty alone was a $211 billion industry, and it continues to grow rapidly.

No question, people would rather worship someone beautiful than criticize the individual or reveal that person’s flaws. Yet beauty shouldn’t serve as a shield for one’s actions as it did for Salomé. But somehow it still does. It’s not hard to explain why a beautiful man or woman can get away with having an outrageous demand satisfied and a far less attractive person cannot. This practice, one naïvely hopes, will somehow start to steadily fade away.

_____________________

Notes:

1. Huysmans, Joris-Karl, “À Rebours” (Against Nature), 1884, translation: Brendan King, p. 81.

2. Lloyd, Joe, “Studio International”,a 1-22-20 review of the “Huysmans, Art Critic: From Degas to Grünewald, in the Eye of Francesco Vezzoli” exhibition.

3. Grigorian, Natasha, “Writings of Joris-Karl Huysmans and Gustave Moreau’s Paintings: Affinity of Divergence”; p. 294.

4. Ob. cit.; p.286.

About the Article

Exploring artists’ views of the consequences of Salomé’s self-centered confrontation with John the Baptist.