With the recent reemergence of populist political support throughout Europe—from the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom, to the rejection of the Renzi reforms in Italy, to rising support for the National Front in France—, it would seem only justified to associate populism as synonymous to far-right wing.

However, the political movement that has grown out the 2016 US Presidential elections backing Democrat Bernie Sanders evidenced an example of populist rhetoric not being unique to the right wing. As populism in itself is not an ideology, therefore cannot be linked to one side of the political spectrum or the other. Populist movements claim to embody the sovereign will of the people, while rejecting the ruling elites. They advocate a political mode that is radically different from that of established democratic systems, sanctifying « the people » as the only valid source of knowledge about what government should do.

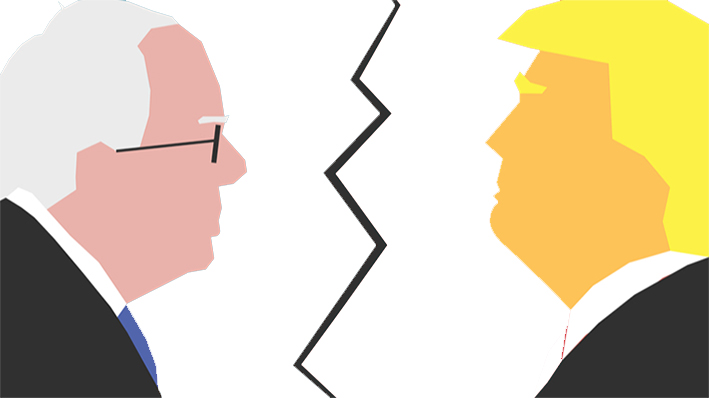

The 2016 US Presidential elections portrayed an undeniable peculiarity in this unprecedented support for a general populist agenda on both the Republican and Democrat ballots. In the first primaries of the campaign, two candidates, on opposite ends of the spectrum, who were only barely members of their respective parties won the Democratic and Republican contests by a landslide. But how can we explain the parallel rise of divergent populist support behind both Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump?

RHETORIC OF “WE”

A key feature of any populist leader mobilizing a movement is the construction of a “we”— “us”, the common people or “silent majority”, versus “them”, the elite. Both presidential candidates led campaigns that supposedly would sovereignty back to the people— and centered on anti-establishment sentiment and collectivism.

M-Sur/Shutterstock.com

Political scientists Kirk A. Hawkins and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser defined populism as: “a discourse that sees politics as a high-stakes struggle between the putative will of a common people and an elite that knowingly conspires against that people for its selfish interests” (Hawkins). This is firstly demonstrated in an evaluation of their use of populist discourse during campaign speeches.

Just as Bernie Sanders railed against “the political and economic establishment,” which had created a “corrupt campaign finance system” and a “rigged economy,” promising to bring back control to “ordinary Americans”, Trump assured his intent to “take back America” from the “corrupt Washington establishment” and “drain the swamp” as he declared to be “transferring power and give it back to […] the [American] people” (Kazin).

OUTSIDER IDENTITY

Both Sanders and Trump parallel as populists by claiming legitimacy for their leadership via the “outsider” identity. Populist movements often embrace the characteristic of a single, providential, usually charismatic leader able to mobilize masses by appealing to their emotions and gain more legitimacy than the established institutions of democracy. Their supporters favor the personal power exerted by strong and charismatic leadership thought to reflect the will of the people.

M-Sur/Shutterstock.com

This sentiment has notably been pertinent amongst today’s youth. 33% of young Europeans and 43% of young Americans support the idea of « being led by a strong man who doesn’t have to worry about parliaments or elections » (Muxel). Trump’s rhetoric taps into some of the same populist anti-elite anger articulated by Bernie Sanders. Trump’s populism is rooted in claims that he is an outsider to D.C. politics, a self-made billionaire leading an insurgency movement on behalf of ordinary Americans just as Sanders’ campaign emphasized his position as the consummate political outsider, his support rooting from a grassroots dynamic, with systemic goals such as bringing down Wall Street.

TIMING— CRISIS AN OPPORTUNITY

2016 was such a fruitful time for populist appeal on both sides of the spectrum in the U.S. because populism often appears in times of uncertainty or crisis, when leaders in place are viewed as unable to cater to those who feel disadvantaged or ignored. The unanticipated popularity of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders has been largely linked to a massive wave of voter discontent with the governing classes.

A recent study of over eight hundred elections in twenty advanced economies found that overall voters tend to polarize by shifting their support towards populist candidates after a serious economic crisis (Hawkins). By 2016, the U.S. was well into recovery from the 2008 financial crisis, resulting in many blue-collar workers being left behind and low income-areas experiencing job loss due to outsourcing and automation. Just as Trump catered blue collar workers who felt betrayed, promising to bring back jobs, Sanders capitalized on those that felt the Democratic party had entirely neglected them.

ONE DISCONTENT; TWO IDEOLOGIES

Trump’s nationalist rhetoric diverges from the roots of U.S. populism: the People’s party. Appealing to white working- and middle-class Americans, it resembles more the Know Nothing party, blaming immigrants for taking Americans’ jobs and breaking the nation’s laws.

The original Populists hold little resemblance to Trump but encompassed far more the concerns of Sanders attacking “the billionaire class,” that led to “an enormous transfer of wealth from the middle class and the poor to the wealthiest in this country.” How can the same term describe a liberal senator from Vermont, a so-called socialist, and a billionaire New York real estate developer who focused much of his campaign on nationalism and anti-immigration? Reading Fukiyama, “Against Identity Politics”, showed there has been much historical debate amongst political scientists as to whether populism be addressed as an ideology (Fukiyama). Political scientist Cas Mudde defined populism by coining the notion of “thin ideology”— without “a programmatic core that is based on the symbolic division of society into two antagonistic groups” (Mudde): ‘the virtuous people’ and ‘the evil elite’. This theory demonstrates that populism rarely exists in isolation— it ascribes itself to host-ideologies reflected in the rise of the two candidates on opposite ends of the spectrum.

Through divergent ideologies, both channel a common rise in discontent with the current system to lead supporters towards more extreme political leanings.

CONCLUSION

2016 reflected a global rise in populism that includes far right-wing parties such as Nationalist Alternative for Germany, Brexit in the United Kingdom and the League in Italy as some of the leading voices. Yet one must dissociate populism from being synonymous to far-right politics. As both Trump and Sanders discovered, the root of the movement comes not from an idealized political belief but from people who feel neglected by the current direction of the evolving world. The 2016 US Presidential elections therefore demonstrated that populism is in no way limited to a far-right phenomenon.

Arthimedes/Shutterstock.com

Bibliography

Darling, Jill, and Margaret Gatz. “Through the Lens of Populism: The 2016 Election.” USC Schaeffer, 28 Oct. 2019, healthpolicy.usc.edu/evidence-base/lens-populism-2016-election/.

Fraser, Nancy. “Progressive Neoliberalism versus Reactionary Populism: A Hobson’s Choice: The Great Regression.” Diegrosseregression.de, sv_redaktion, 13 Apr. 2017, www.thegreatregression.eu/progressive-neoliberalism-versus-reactionary-populism-a-hobsons-choice/.

Fukuyama, Francis. “Against Identity Politics.” The Andrea Mitchell Center for the Study of Democracy, 2018, www.sas.upenn.edu/andrea-mitchell-center/francis-fukuyama-against-identity-politics.

Hawkins, Kirk A., and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. “Measuring Populist Discourse in the United States and Beyond.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 2 Apr. 2018, www.nature.com/articles/s41562-018-0339-y.

Hawkins, Kirk, and Levente Littvay. “Contemporary US Populism in Comparative Perspective by Kirk Hawkins.” Cambridge Core, Cambridge University Press, 2019, www.cambridge.org/core/elements/contemporary-us-populism-in-comparative-perspective/8D5577EECBE831206721B23CFA35A9F8.

Hirschauer, John. “The Unpopular Populist.” National Review, National Review, 9 Mar. 2020, www.nationalreview.com/2020/03/the-unpopular-populist/.

Kazin, Michael. “How Can Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders Both Be ‘Populist’?” The New York Times, The New York Times, 22 Mar. 2016, www.nytimes.com/2016/03/27/magazine/how-can-donald-trump-and-bernie-sanders-both-be-populist.html.

Mudde, Cas (2004). ‘The Populist Zeitgeist’, Government and Opposition, 39:4, 541-563

Muxel, Anne. “Declining Trust in Democracy Between Generations.” What next for Democracy?: an International Survey by the Fondation Pour L’innovation Politique, by Dominique Reynié, Fondation Pour L’innovation Politique, 2017.

Oliver, J. Eric, and Wendy M. Rahn. “Rise of the Trumpenvolk: Populism in the 2016 Election.” Shibboleth Authentication Request, 16 Aug. 2016, journals-sagepub-com.acces-distant.sciencespo.fr/doi/full/10.1177/0002716216662639.

Pierson, Paul. “American Hybrid: Donald Trump and the Strange Merger of Populism and Plutocracy.” Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 8 Nov. 2017, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1468-4446.12323.

Schoen, Douglas. “Why Populism Is Back in Full Force.” TheHill, The Hill, 15 Sept. 2019, thehill.com/opinion/international/461450-why-populism-is-back-in-full-force.

About the Article

A look at how populism this decade has sprung up on both the left and the right.