Everett-Art/I.Golovinov/Shutterstock.com

All artists are not just artists. A few have also possessed a strong social voice, one that speaks out about the times. A voice clearly needing to be heard.

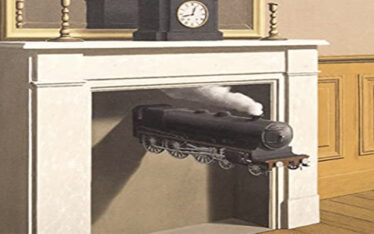

DEGAS & LAUTREC

More than a century before the Me Too Movement took hold and long before first-rate investigative reporting existed to inform the public at large, women in dance struggled to support themselves and still retain their personal dignity.

In France, almost by default, it was left by chance to accomplished artists such as Edgar Degas and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec to brilliantly expose to the public the degrading conditions that prevailed. Canvases, especially from these two, brought a much needed but pained attention to the women’s plight.

EXPLOITATION

Sexual predators, at the end of the nineteenth century, regularly preyed on women who aspired to succeed in the performing arts. Harvey Weinstein, Jeffrey Epstein, Bill Cosby and the like had far too many unscrupulous precursors.

In order to sustain a career as a dancer or a model, most women in these professions had little choice but to contend with and ultimately give into such dubious behavior. It was part of the price.

DANCERS – LATE 1900S

“Edgar Degas: the most Parisian of all the Impressionists,” according to Jason Farago of the NY Times, was “the super fan par excellence… of the opera and ballet.”

Degas depicted opera dancers at a time when the opera was dependent on the largess of its sponsors. These elder male patrons, in turn, sought out companionship from the young ballerinas. Opera management supposedly encouraged the dancers to oblige so big spenders would readily continue to subsidize their high-priced productions.

Worse yet, “Often, girls’ own mothers –who acted not unlike entertainment agents today– helped set up and maintain these relationships.” History.com reports: “In many Paris Opera ballerinas from poor backgrounds, a relationship with a rich man was their only chance…”

Everett-Art/Shutterstock.com

NOT SO PAST

Decades before the advent of the casting couch, the Paris Opera house had a huge room behind the stage, where the ballet corp practiced and rehearsed. Here, as a reward for generously helping keep the opera afloat, many of the company’s formally clad, elder patrons could mingle with the young dancers, size them up and discreetly arrange for their companionship.

Degas captured every posture, every mood, every aspect of the dancers’ backstage and onstage existence. “He recorded,” according to History.com, “behind-the-scenes views of dancers practicing – and captured the world of the lecherous male subscribers too.”

BACKSTAGE

Everett-Art/Shutterstock.com

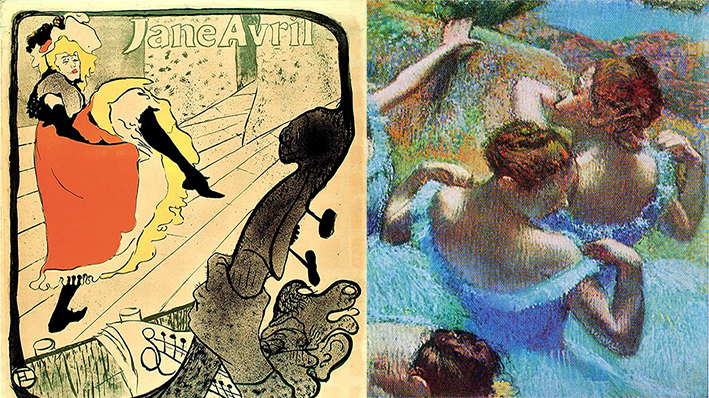

Similarly, most every night one could find Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec seated at his regular table in the Moulin Rouge, a famous club in Montmartre. There, he drank heavily to kill the pain in his passion and his crippled legs while he observed.

“Lautrec compensated for his physical deformities with alcohol and an acerbic, self-deprecating wit.” According to the Metmuseum.org: “His sympathetic fascination with the marginal in society, as well as his keen caricaturist’s eye may be partly explained by his own physical handicap.”

But when he drew, Lautrec miraculously became whole. With rapid strokes, he sketched the provocative and rowdy can-can dancers as they teased, kicking one leg high above their heads. They’d hold it there then rapidly lift the other as skirts and petticoats swirled into a giant pinwheel.

Truly fascinated, Lautrec captured the dancers’ frantic energy and forced smiles. Other times, he would visit behind the scenes to sketch women off-duty at brothels or others fatigued in salons. Loyal to the influence of Post-Impressionism, Lautrec also “stayed true to a vigorous realism”.

Lautrec used his charcoal and brush like a camera, capturing these women with their hair down in their off-hours as they rested, faces free of makeup or bathed, got dressed or stretched their muscles that often were too weary to flex.

FOCUS

Lautrec would zero in on a particular aspect of his subject’s look and use it to emphasize her features. He’d intentionally leave other sections unfinished to direct the viewers eyes to where he wanted them. Often he used a black garment such as elbow-length gloves, knee-high stockings or boots, a delicate choker or a boa-like scarf. He used these prominently emphasized accessories to direct attention to a frozen moment of facial joy or angst or to emphasize a suffering or swollen body.

Lautrec succeeded in humanizing their condition. The women’s suffering, no longer an object, spoke for itself.

About the Article

A view of two late-19th-century artists and the degraded dancers each depicted.